Fashion has been described as the science of appearance, a science that inspires the individual with the desire to “seem” rather than to “be”.

This preoccupation with the superficial makes the clothing industry an endless source of bemusement for most of us mere mortals as we watch the world’s supermodels walk the catwalk in the latest “creation”.

But the obsession with the new and trendy is not confined to clothing designers. Even the investment industry can place greater importance on fashion than science.

Anyone remember technology funds? These highly concentrated investment vehicles were all the rage at the turn of the decade when the silicon chip was seen as a synonym for the blue chip.

These days, though, those investors with technology funds feel like fashion victims with wardrobes full of stone-washed jeans and leg warmers.

The now infamous “tech wreck” of early 2000 sent the exit prices of many of these highly concentrated funds to bargain basement levels, from which they have never emerged.

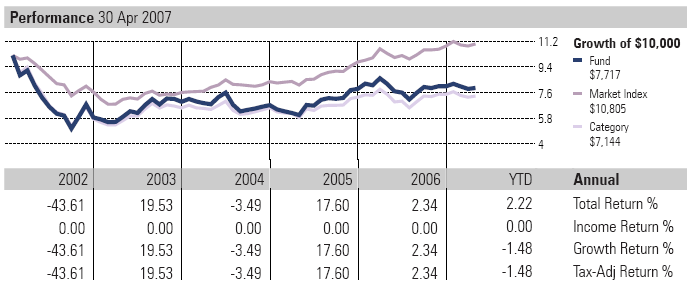

Let’s take the example below of $10,000 invested in the Goldman Sachs JBWere Global Technology Wholesale Fund on 1 May 2000.

Source: Morningstar Research Pty Limited. Analysis: Capital Partners Financial Consulting. Market Index used is the MSCI World Acc Index Net Div Reinvested (AUD).

As we can see the fashion-conscious investor ended the year with 43.6% less capital than they began with, and even now they have not recovered their original capital. Now let’s not forget that our investor has paid a 1.61% per annum expense fee for the privilege of going backwards.

By stark contrast let’s look at an intelligent investor who on the same date, 1 May 2002, invested the same $10,000 in a diversified growth portfolio of Australian and international shares, property and fixed interest investments.

For a start, our intelligent investor has paid a much lower management fee of 0.9% per annum giving a significant advantage right from the word go, but let’s look at the outcome.

At the end of 2000, the diversified portfolio had fallen by 7.18% a far cry from its more fashionable counterparts -43.6%. More importantly, after 5 years the intelligent investor’s portfolio was worth $16,193.

So what observations can we make from this walk down memory lane?

Observation 1: The technology funds spawned from the tech boom were not a one-off phenomenon. As one sector-specific strategy goes out of vogue, you can always count on some new model taking its place on the investor catwalk.

On that score, funds focused on private equity, green energy, water rights, environmental stocks, healthcare issues or infrastructure are just some of the vehicles currently in fashion, or on the drawing boards of our major institutions.

These funds are easy to market to investors because of global trends that appear to reinforce the appeal of their underlying assets—such as concern about global economic imbalances, climate warming or the aging population.

But taking an interest in those worthy public issues at a personal level is one thing. Basing your long-term investment strategy upon them is another.

Observation 2: The reason for caution is that science has shown that building a portfolio on anything other than the known sources of return leaves an investor open to the prospect of taking significant risks that they may never be rewarded for. This is known as diversifiable risk.

This is not some new theory. Financial economists established in the 1950s that less diversified portfolios take on more diversifiable risk. And this is what a bet on technology or infrastructure or green stocks involves.

Sectors can be hot for a year or two, and then turn cold. And if you take big bets on a single sector, you could be taking significant additional risk for no additional return. It’s like building your wardrobe around a passing fad.

An alternative is to stick to an approach that works over the long haul if not every year. In fashion, this is like constructing a wardrobe around a classic blue suit, a white shirt and a pair of black leather shoes.

In investment, the classic approach is based not on vague hunches, but on long-term, disciplined research and rational expectations.

This approach1 says that higher expected returns come from equities over bonds, from small-cap stocks over large-cap stocks and value stocks over growth stocks. Together these three factors explain some 95 per cent of the variation in portfolio returns.

Expected returns from those three factors are higher because of the higher risks involved in each. And as these are non-diversifiable risk factors, they should be the building blocks of your investment portfolio.

This approach might not be fashionable. However, it is an intelligent, reliable way of focusing on the factors of investment returns while reducing excess and undesirable risk.

Time for a makeover?

1Fama, Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French. 1992. The cross-section of expected stock returns. Journal of Finance 47 (June): 427-465.